Professor of Law, Villanova University

Ana Santos Rutschman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

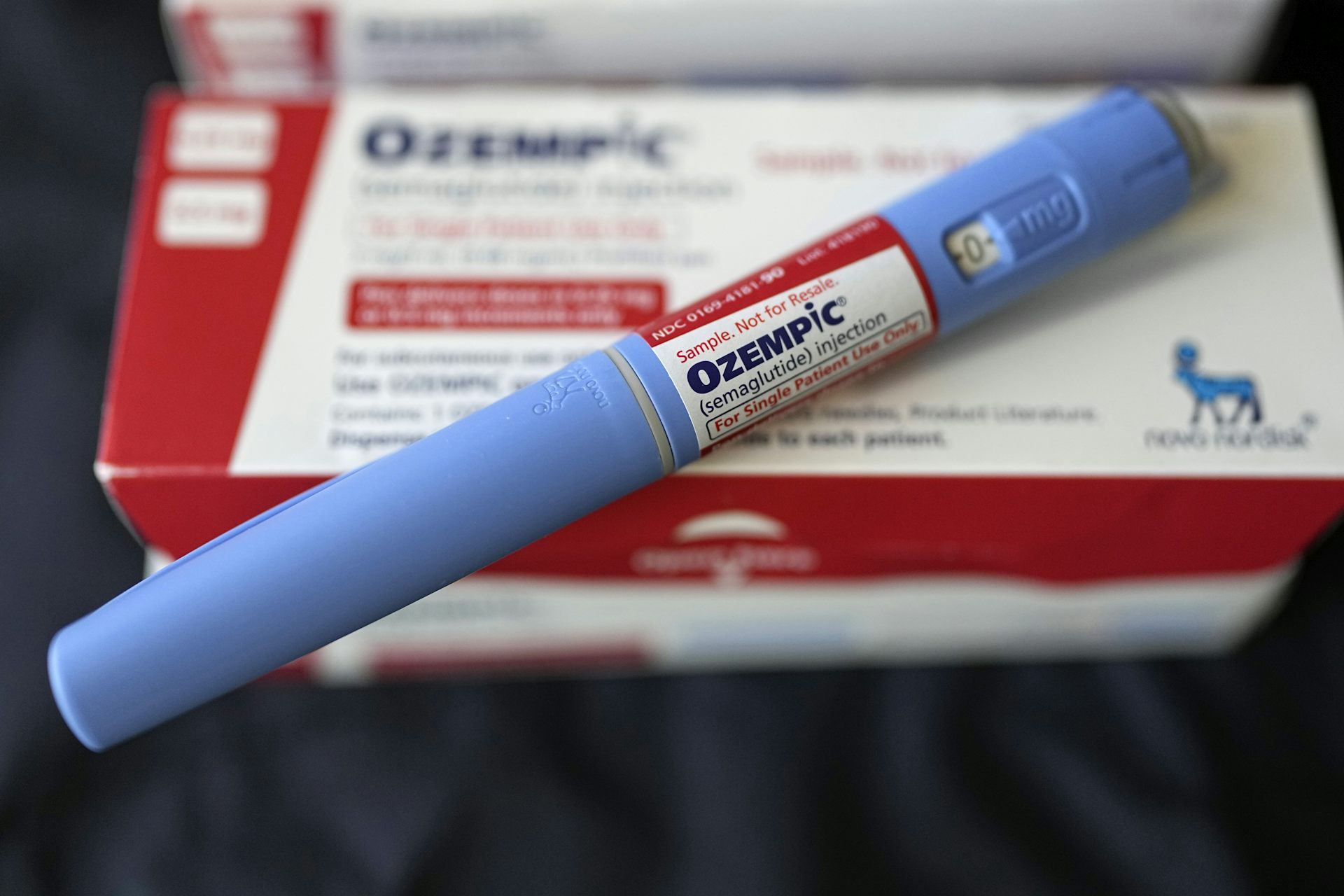

The manufacturers of the most popular weight loss drugs are being challenged in court.

A federal court in Philadelphia will soon evaluate claims against the makers of Ozempic, Wegovy and similar products.

Dozens of patients who suffered gastrointestinal problems after taking these drugs brought lawsuits alleging that these companies failed to properly warn patients about the risks.

Weight loss drugs are among the most successful products sold in the U.S., with prescriptions rising fortyfold from 2018 to 2023. Scientific studies have backed up their safety and efficacy, and doctors prescribe them for a variety of reasons, including to lower the risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular events.

Over the past few years, celebrities and word of mouth made these drugs go viral on social media. More than 15 million Americans have reported using these drugs as of May 2024.

So, what do patients’ claims about the risks associated with weight loss drugs mean for the future of these products? I’m a health law professor who studies pharmaceutical drug regulation and access to medicines, and I’ve been watching the legal developments closely. Regardless of how the trial turns out, I think it could have a big impact on public trust and on the market for weight loss drugs.

Several types of medications fall under the umbrella of “weight loss drugs.” The five drugs at stake in the lawsuit belong to the same class: GLP-1 agonists or analogs, short for glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. GLP-1 agonist drugs help manage blood sugar levels. They were originally approved for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes.

These drugs make people feel full. Doctors started prescribing them for weight management even before the FDA approved them for that purpose. This is a practice known as off-label prescribing. Off-label prescribing is legal and accounts for more than 20% of prescribing activity in the United States.

The Danish company Novo Nordisk makes Ozempic, Wegovy and Rybelsus. The American company Eli Lilly makes Trulicity and Mounjaro.

In 2023, Eli Lilly became the world’s most valuable pharmaceutical company. Sales of Trulicity and Mounjaro played a large role in making that happen. For instance, in 2023, sales of Mounjaro surpassed US$1 billion per quarter. Eli Lilly and analysts alike predict that revenue from the company’s weight loss drug will rise substantially between 2024 and 2030.

Novo Nordisk has also made a mint on weight loss drugs. Its sales of Ozempic, Wegovy and Rybelsus have made it the most valuable company by market capitalization in Europe. It is currently more valuable than companies such as Tesla and Visa and has been described by one reporter as the “single company propping up” the entire Danish economy.

The lawsuit consolidates dozens of cases brought by patients who took one of these five drugs. They were consolidated partly because the legal grounds for all these cases were similar. The trial is happening in Pennsylvania because that was the state with the most pending legal actions. Also, Novo Nordisk’s U.S. headquarters are located nearby in New Jersey.

The patients in the lawsuit each took one of the drugs described above. They all suffered gastrointestinal or related problems. These include intestinal obstructions and gastroparesis, a slowing or halting of the movement of food in the stomach.

On the medical side of things, the patients allege that these drugs increase the risk of gastrointestinal injuries. On the legal side, they allege that the companies failed to properly warn patients of the risks. The lawsuit also raises the question of whether the companies made incomplete or misleading representations about these drugs. The companies have signaled that they will challenge these claims.

We won’t know the outcome of the case for a while. But this lawsuit will have immediate implications.

First, it brings attention to the risks associated with these popular drugs. Recent studies have shown that the use of GLP-1 agonists is associated with higher rates of gastroparesis, intestinal blockages and pancreatitis. These problems, and many others, including an increased risk of certain tumors, are listed as potential side effects both by the companies and the FDA.

The lawsuit will likely remind people that no drug is free of risk and that patients need to be aware of these risks before and during treatment.

Second, while these drugs present risks, the FDA has reviewed the best available scientific evidence, performed a benefit-risk analysis and decided that the benefits are worth the risk.

For the past decade, however, the FDA’s credibility has been under attack. Conspiracy theories about the agency abound on social media. The FDA is often the target of baseless accusations that it approves harmful drugs and suppresses good ones.

A major legal challenge to weight loss drugs could contribute to the ongoing erosion of trust in the FDA itself. And in an era of misinformation, conspiracy theorists could use the lawsuit to improperly suggest that these, or all, FDA-approved drugs are bad or unsafe.

Finally, less trust in weight loss drugs may eventually lead to a decline in demand. In the past, litigation and misinformation have caused sales declines, which in turn prompted manufacturers to stop making some drugs. This was the case with a Lyme disease vaccine that was approved by the FDA in 1998 and discontinued in 2002 because of low sales. Since then, Lyme disease vaccines for dogs have been brought to market, but humans still can’t get one.

While sales of weight loss drugs are currently stratospheric, sometimes a seemingly isolated event such as a lawsuit can set in motion cascading long-term effects.

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 185,900 academics and researchers from 4,984 institutions.

Register now

Copyright © 2010–2024, The Conversation US, Inc.